Interdisciplinary Research Seminar: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies – the University of Toronto, November 14, 2012

“The Eucharist and the Negotiation of Orthodoxy in the High Middle Ages”

Adam Hoose

From the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies:Adam Hoose defended his dissertation at Saint Louis University on “Orthopraxy and the formation of the early Waldensians and Franciscans, 1173–1228.” He has been an adjunct instructor in history at St Louis University and Lindenwood University. His most recent publication is “Francis of Assisi’s Way of Peace? His Conversion and Mission to Egypt,” Catholic Historical Review 9 (2010): 435–55. His Mellon Research project is entitled “Negotiating Orthodoxy: The Early Waldensians and Franciscans, 1173–1228.”

Summary

This paper is part of Adam Hoose’s dissertation. It examined the differences between Waldensians and Franciscans in their treatment of the Eucharist. It also explored why the Waldensians were unsuccessful in their bid to become a legitimate religious order and were eventually marginalized as heretics.

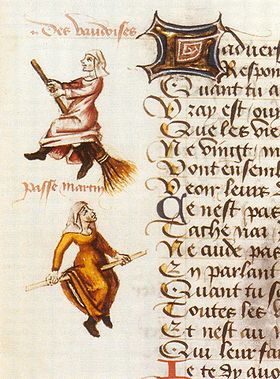

Hoose began his talk with the Waldensian sect of the Reconciled Poors. Waldensians and Franciscans were part of a lay religious movement from the 12th and early 13th centuries.

The emergence of heresy in the high Middle Ages: The clergy perceived heresy as an “us vs. them” attitude. We know very little from sources on Waldensians; most resources were hostile to Peter Waldo and his followers. One account, an exempla from the abbey of Clairveaux, was not hostile to him and spoke of his conversion. However, this exempla has its own set of problems. We know very little about Waldo’s conversion and early followers. After his conversion, the sources are still somewhat muddled. One account claims he put his daughters in a convent and that he ran a soup kitchen. Waldo eventually went to Rome for an audience with Pope Alexander III to obtain permission to continue preaching. The Pope only granted him conditional permission to preach and it was contingent on the clergy’e permission around him. There were complaints about Waldo preaching without permission and that Waldensians lived sinfully. They were often condemned by secular authorities.

Waldensians were staunch defenders of the Catholic faith and the Eucharist against groups like the Cathars. During Innocent III’s reign, their problems came to a head. The Waldensians were also divided amongst themselves over the question of who could celebrate the Eucharist and multiple “Waldensianisms” appeared.

What we lack in information for the early Waldensians, we have an over abundance of sources for the early Franciscans. The sources are very “friendly” toward the order and hagiographical in nature. The earliest hagiography was written in 1228. It was based on those who knew Francis and on his deathbed testament in 1226. This work was also problematic. In 1261, the Franciscan General Chapter commissioned an official hagiography of St. Francis and ordered all previous works destroyed. Hoose briefly gave an overview of Francis’s life, conversion, life as a hermit, and the development of the order. Francis committed himself to a life of penitential poverty. The Franciscans also went to the Pope obtain permission to continue preaching, however, unlike the Waldensians, they received approval. There was some controversy in the early beginnings of the order over how they should live, the interpretation of Francis’s idea of poverty, etc…

Why did the Pope approve the Franciscans but not the Waldensians? Their practices didn’t conform to the church and they continued to preach without permission, therefore, their behaviour was declared deviant. The Friars Minor, although not without their own misunderstandings, followed doctrine listened to and respected the clergy. For the clergy, the most important need was to safeguard the sacraments and the people from the Waldensians, in spite of the fact that Waldensians claimed to be defenders of the Catholic Church.

The earliest Waldensian sources show a strong belief in the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. They drew on Peter Lombards’ “Sentences” to respond to the Cathars and explain how evil men could consume the Eucharist. Nothing here was heretical or deviated from Orthodoxy. Is this treatise indicative of Waldensians at all? It is quite probable that this was written by Waldo. He did share this belief in the presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

St. Francis and the Eucharist – although he was known for his preaching, he spent a lot of time writing about the Eucharist. He repeatedly expressed concern about the use of liturgical instruments, the cleaning of tools used for Mass and the handling of the Eucharist. Both groups seemed to have shared a very similar view of the Eucharist. There has been a lot of research produced recently on Eucharistic work. Waldensian liturgy can be seen as liturgical renewal of the interpretation of the Eucharist. Waldensians were also divided between those who believed a Roman priest was necessary vs. those who believed any worthy Christian could celebrate the Eucharist. Innocent III wanted them to discard this latter view.

In contrast, the Franciscans had a profoundly strong respect for Catholic clergy. Waldensians affirmed the necessity of priests for the performance of Mass, however, they did not have any clergy themselves. Waldensians were obliged to listen to the bishops unless the bishop was doing something that was contrary to doctrine. Waldo didn’t reject that a priest was needed to consecrate the Eucharist, but there were various levels of requiring the Waldensians to obey. They clergy criticized the Waldensians for neglecting to work because they preached instead. Canon law prohibited unsanctioned preaching. The Waldensians were considered a threat to clerical authority because they preached without Papal permission and Waldensians believed God had called them to preach where the clergy had failed.

Confession and penance – the Waldensians were accused of discarding the necessity of priests for confession, whereas Francis exhorted his followers to confess to priests. The Franciscan insistence on manual labour and the Waldensian insistence on preaching were where they differed – the Waldensians believed that preaching was work, the work of God.

Tune in on Wednesday, November 21st as we report on another great session entitled: “Exploring the Connections between Metaphysics and Political Thought in the Age of Wyclif and the Conciliarists”, given by Alexander Russell at the Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies, at the University of Toronto.

Interdisciplinary Research Seminar: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies – the University of Toronto, November 14, 2012

“The Eucharist and the Negotiation of Orthodoxy in the High Middle Ages”

Adam Hoose

From the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies: Adam Hoose defended his dissertation at Saint Louis University on “Orthopraxy and the formation of the early Waldensians and Franciscans, 1173–1228.” He has been an adjunct instructor in history at St Louis University and Lindenwood University. His most recent publication is “Francis of Assisi’s Way of Peace? His Conversion and Mission to Egypt,” Catholic Historical Review 9 (2010): 435–55. His Mellon Research project is entitled “Negotiating Orthodoxy: The Early Waldensians and Franciscans, 1173–1228.”

Summary

This paper is part of Adam Hoose’s dissertation. It examined the differences between Waldensians and Franciscans in their treatment of the Eucharist. It also explored why the Waldensians were unsuccessful in their bid to become a legitimate religious order and were eventually marginalized as heretics.

Hoose began his talk with the Waldensian sect of the Reconciled Poors. Waldensians and Franciscans were part of a lay religious movement from the 12th and early 13th centuries.

The emergence of heresy in the high Middle Ages: The clergy perceived heresy as an “us vs. them” attitude. We know very little from sources on Waldensians; most resources were hostile to Peter Waldo and his followers. One account, an exempla from the abbey of Clairveaux, was not hostile to him and spoke of his conversion. However, this exempla has its own set of problems. We know very little about Waldo’s conversion and early followers. After his conversion, the sources are still somewhat muddled. One account claims he put his daughters in a convent and that he ran a soup kitchen. Waldo eventually went to Rome for an audience with Pope Alexander III to obtain permission to continue preaching. The Pope only granted him conditional permission to preach and it was contingent on the clergy’e permission around him. There were complaints about Waldo preaching without permission and that Waldensians lived sinfully. They were often condemned by secular authorities.

Waldensians were staunch defenders of the Catholic faith and the Eucharist against groups like the Cathars. During Innocent III’s reign, their problems came to a head. The Waldensians were also divided amongst themselves over the question of who could celebrate the Eucharist and multiple “Waldensianisms” appeared.

What we lack in information for the early Waldensians, we have an over abundance of sources for the early Franciscans. The sources are very “friendly” toward the order and hagiographical in nature. The earliest hagiography was written in 1228. It was based on those who knew Francis and on his deathbed testament in 1226. This work was also problematic. In 1261, the Franciscan General Chapter commissioned an official hagiography of St. Francis and ordered all previous works destroyed. Hoose briefly gave an overview of Francis’s life, conversion, life as a hermit, and the development of the order. Francis committed himself to a life of penitential poverty. The Franciscans also went to the Pope obtain permission to continue preaching, however, unlike the Waldensians, they received approval. There was some controversy in the early beginnings of the order over how they should live, the interpretation of Francis’s idea of poverty, etc…

Why did the Pope approve the Franciscans but not the Waldensians? Their practices didn’t conform to the church and they continued to preach without permission, therefore, their behaviour was declared deviant. The Friars Minor, although not without their own misunderstandings, followed doctrine listened to and respected the clergy. For the clergy, the most important need was to safeguard the sacraments and the people from the Waldensians, in spite of the fact that Waldensians claimed to be defenders of the Catholic Church.

The earliest Waldensian sources show a strong belief in the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. They drew on Peter Lombards’ “Sentences” to respond to the Cathars and explain how evil men could consume the Eucharist. Nothing here was heretical or deviated from Orthodoxy. Is this treatise indicative of Waldensians at all? It is quite probable that this was written by Waldo. He did share this belief in the presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

St. Francis and the Eucharist – although he was known for his preaching, he spent a lot of time writing about the Eucharist. He repeatedly expressed concern about the use of liturgical instruments, the cleaning of tools used for Mass and the handling of the Eucharist. Both groups seemed to have shared a very similar view of the Eucharist. There has been a lot of research produced recently on Eucharistic work. Waldensian liturgy can be seen as liturgical renewal of the interpretation of the Eucharist. Waldensians were also divided between those who believed a Roman priest was necessary vs. those who believed any worthy Christian could celebrate the Eucharist. Innocent III wanted them to discard this latter view.

Confession and penance – the Waldensians were accused of discarding the necessity of priests for confession, whereas Francis exhorted his followers to confess to priests. The Franciscan insistence on manual labour and the Waldensian insistence on preaching were where they differed – the Waldensians believed that preaching was work, the work of God.

Tune in on Wednesday, November 21st as we report on another great session entitled: “Exploring the Connections between Metaphysics and Political Thought in the Age of Wyclif and the Conciliarists”, given by Alexander Russell at the Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies, at the University of Toronto.

~Sandra Alvarez

Subscribe to Medievalverse

Related Posts